Who were Hitler’s « executioners »?

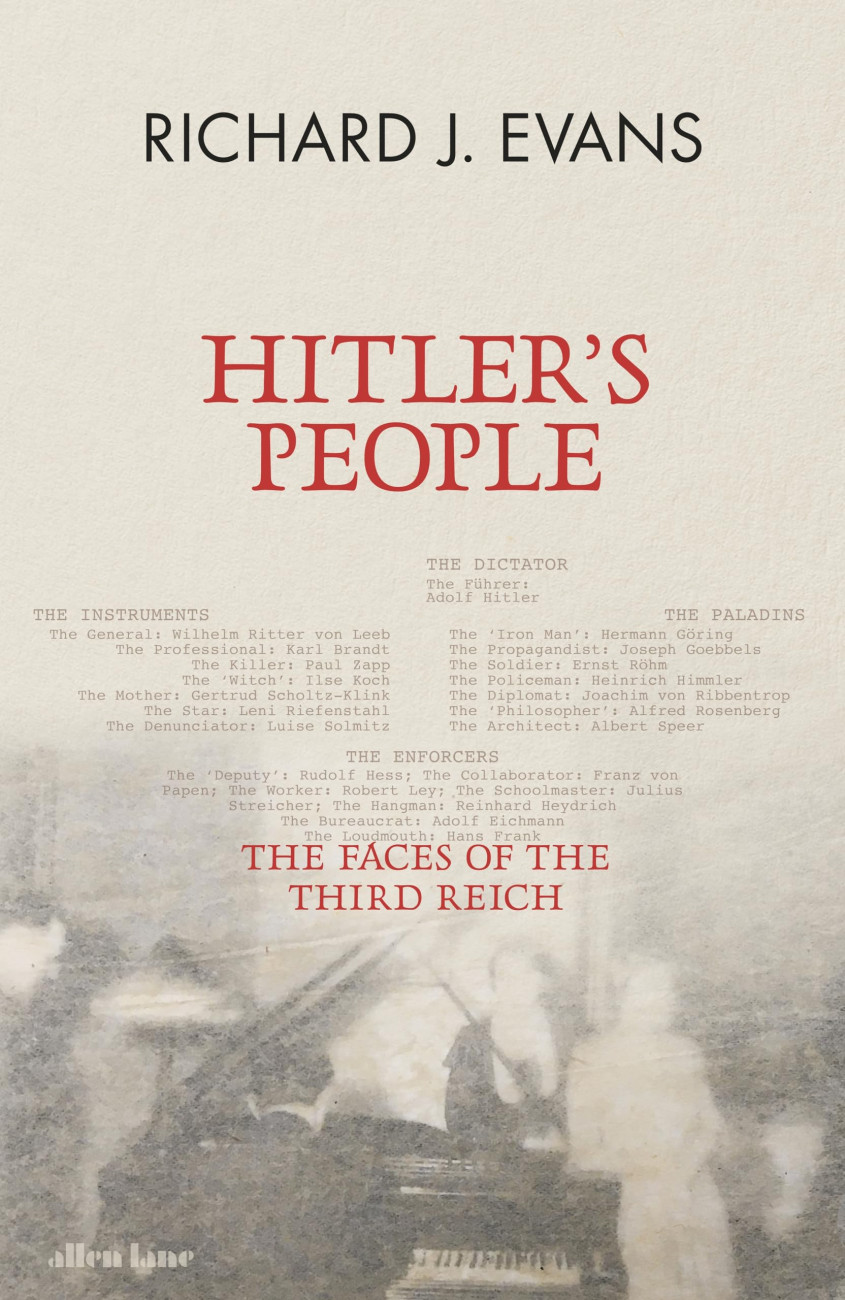

« We know who the men and women who served Adolf Hitler were. We know what they did … What we don’t know is what prompted them to do it. » In this way, Neil Aserson begins his book review for the newest title of important historian Richard Evans « Hitler’s People: The Faces of the Third Reich » in his recent issue New York Review of Books (« Ordinary Germans »). Evans indicates and the critic agrees that the Nazi At the time it was not what Christopher Browning defined as « everyday people » in 1992. On the contrary, « the police (who participated in the clearances) were volunteers » and « were carefully selected according to ideological criteria – their education was based on strong doses of Nazi and Nazi. » They were not only the « Germans of the next door », but Germans who lived in the buzz and the loser of a defeated country after World War I believe in multiple conspiracy theories, which Hitler would later be tool.

Who were Hitler’s « executioners »?

The title of Evans is essentially added to the separate category of books on the Third Reich that are investigating exactly this: the material from which the « servants » and executioners of the Nazi machine were made. And here is, as is well known, the title of Daniel Goldhagen « The Eastern executioners of Hitler » (1996), mentioned by Aserson for the reactions he caused when he was released. Goldhagen claimed there that anti -Semitism and desire for a dictatorship were inherent elements of German identity. That is, the nation was presented as a collective monster because of a historical uniqueness. It was a perception open to criticism, as can be seen from the reference to the leading historian Saul Friedlender in « Nazi Germany and the Jews » (Polis ed. They were murdered was not necessarily the result of a deeply rooted and historically unique German anti -Jewish passion, as Daniel Jonah Goldhagen argued. Nor was it mainly the result of a wide range of social and psychological restrictions, aids and dynamics processes of the group independent of ideological motives, as Christopher R. Browning believes. The Nazi system as a whole had produced an « anti -Jewish culture » which … was cultivated by all the means at its disposal … Perhaps the « ordinary Germans » had some vague awareness of the process. Most likely, however, they have interpreted the anti -Jewish representations and beliefs, without recognizing that it was an ideology that would be systematically accentuated by state propaganda and all the means she had at her disposal. «

Lighting Lawrence Reese in his own book entitled « The Dark gift of Adolf Hitler » (ed. Patakis, ed. Ourania Papaconstantopoulou, 2016): « How is it possible Effectively the financial crisis … The feeling that under the authority of a « strong man » the country would finally be involved. The belief that that « difficult (economic) juncture » required « solidarity » was the motivation for Fritz Arlt, an eighteen -year -old student in 1930, to join the Nazi party. Influenced by his big brother, he had been flirting with the ideology of Marxism for a while, but now he felt that « socialist solidarity » was impossible inside and outside the border, as the other states were now focused on their own national interests. » In addition, in the « Maenades of Hitler » (ed. Metachimo, Alexis Kalofolias, 2014) on the role of Germans in the Nazi extermination fields, Wendy Loweer points out that « they were not some marginal psychopaths with antisocial tendencies. They believed that their crimes were justified acts of revenge imposed on the Reich enemies. «

Especially for youth on Nazism, a view is given by Conrad Jaras in the ‘Broken Lives – How Ordinary Germans Experienced The 20th Century ”(Princeton University Press, 2018):“ Young people are supposed to create a distinct identity, away from their parents and found a new orientation with their peers. Hitler youth met such needs by offering young people their own mission so that they are missing from home and finding their own age group. «

This discussion could not miss a reference to Hannah Arend. In Evans’ chapter for Adolf Eichmann, the historian defends the perception of the « community of evil » in a different light: « This expression was greatly misinterpreted and even consciously. With the « community of evil » he did not mean that Eichmann was simply a bureaucrat … For Arendt, he was a typical type of executors in regimes such as Hitler or Stalin: moderation without independent or creative thought. » This view agrees with one more that Evans develops in his book: « There were many Germans, not fanatics of Nazis, who supported Nazism because they have implemented many of their desires and ambitions to overlook other parameters. » An example of this was the social welfare programs (« power through joy ») implemented by Robert Lai, head of the Nazi work front, through which cruises and cultural activities for workers were organized.