Koteletts from the eighties – Diepresse.com

In « no little thing » the mother is busy freezing and nagging, the father with lamas and cats. And the daughter? Annoyed by the drama.

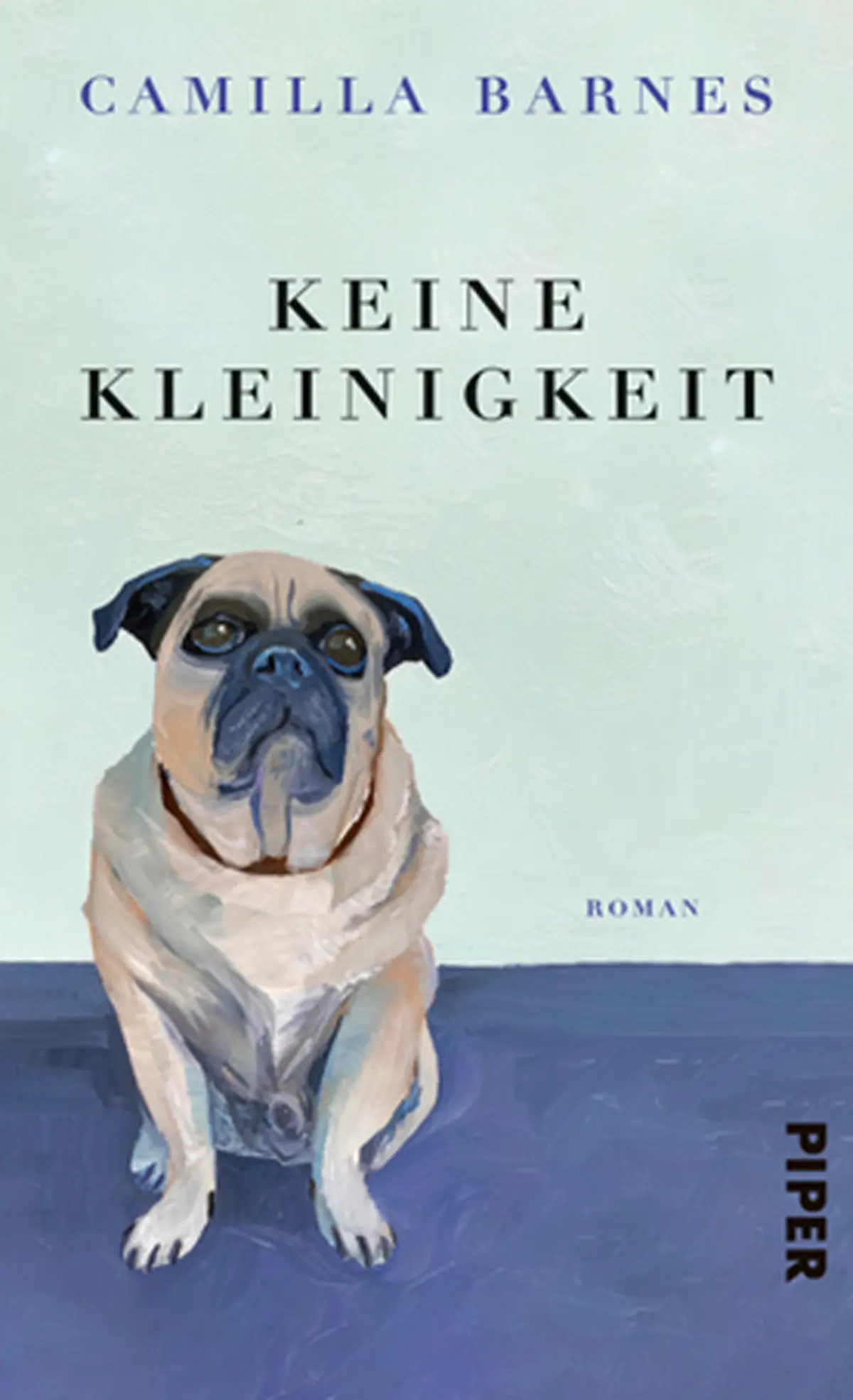

« /> Camilla Barnes: « No little thing », translated by Dirk van Gunsteren, Piper-Verlag, 256 pages, 25.50 euros

Is that really like that? The tragedies of the young years, the missed occasions and unfortunate decisions are reflected in the spleens of age? This thesis traces Camilla Barnes, born in 1969, in her debut. She zooms in the everyday life of an eccentric English couple in his seventies and breaks complex family dynamics light -footed to fast -footed, funny dialogues between the door and angel. Her youngest daughter Miranda, a final forty, takes the observation perspective.

Miranda once wanted to bring a distance between herself and her family. She returned to England to become a « competent but uninspired » actress in Paris. Hardly in retirement, father and mother promptly followed her and settled in the French province.

The traces of 50 years of marriage

Driven by the feeling that she should « want to visit her parents », Miranda is regularly drawn in their bizarre struggles between stubbornness and pedantry on the weekends. After more than fifty years of marriage, the Oxford are caught in their peculiarities. He is more interested in his llamas, cats and ducks than for humans and is compliantly commanding « because he is too tedious for him ». She has to complain about everything, first deals with stocks and quotes French poems (typically in her evening « drinks »).

At Camilla Barnes, all of these peculiarities prove to be no small things at all – analogous to the well -chosen German title (original: « The Usual Desire to Kill »). Especially the mother’s obsession of preserving food runs like a thread through the novel. Your credo: once frozen, nothing spoils. The family is already served in 1983 without twitching with the eyelash (the old freezer and content, of course, came along). Similar to food, the mother also hoard the past, is completely focused on it – so much that she sometimes forgets the present (her daughters and their interests). She reliably steers the conversation to war, although she didn’t notice any of it. Happiness? Not for Miranda’s mother, who has to struggle with her uneventful past anyway: « The war – also something that I missed. »

The author and Miranda connects biographical: both grew up in Oxford, live in Paris, work on the theater and adapt English pieces. This proximity to the theater makes the novel, in which nothing and everything happens equally and everything happens – even if the staged staged initially takes some getting used to. On the one hand there are the many tragic-comic conversations in which sentences such as tennis balls are shot back and forth, on the other hand, scenes with exclusively dialogues and directing instructions (brought into German by TC Boyle translator Dirk van Gunsteren). Further formal breaks in the story are the emails between Miranda and the sister remaining in England and the mother’s old letters to an ominous kitty.

The parents are silent

A lot is ominous in the family tree of this family. How about the unknown great uncle? What about the mother’s fictional child? And what secret is the « incident » behind the decades, which is only hinted at today? But the memories of the parents are not reliable, wanting to end their willingness to provide information.

The mother’s letters tempt you to search for the traces of the woman from back then. But Barnes plays with the readers. It gradually opens new doors that only lead into the dark, and scattered crumbs more pregnant – since a literary allusion, a historical reference. Once in good hands, they throw new light on an aspect of history, in order to dissolve in nothing. Only towards the end do other perspectives flash, such as the relentless look of Miranda’s daughter Alice on her mother.

That’s how it is with families and generations. Biographies are contradictory, relationships are complicated, deceive memories and the appearance is deceptive. Barnes succeeds in woving off the past with the fleeting bizarre of the present. There was still light and sounded here, and life continues. Everything just theater?