How indo -European conquered the world – the press.com

Only a few people spoke the preform of the most important language family today in today’s Ukraine. How did she spread? Through violence, culture or illness? In the new book « The Big Bang of our Languages » Laura Spinney treats this success story – unfortunately sometimes too dreamy.

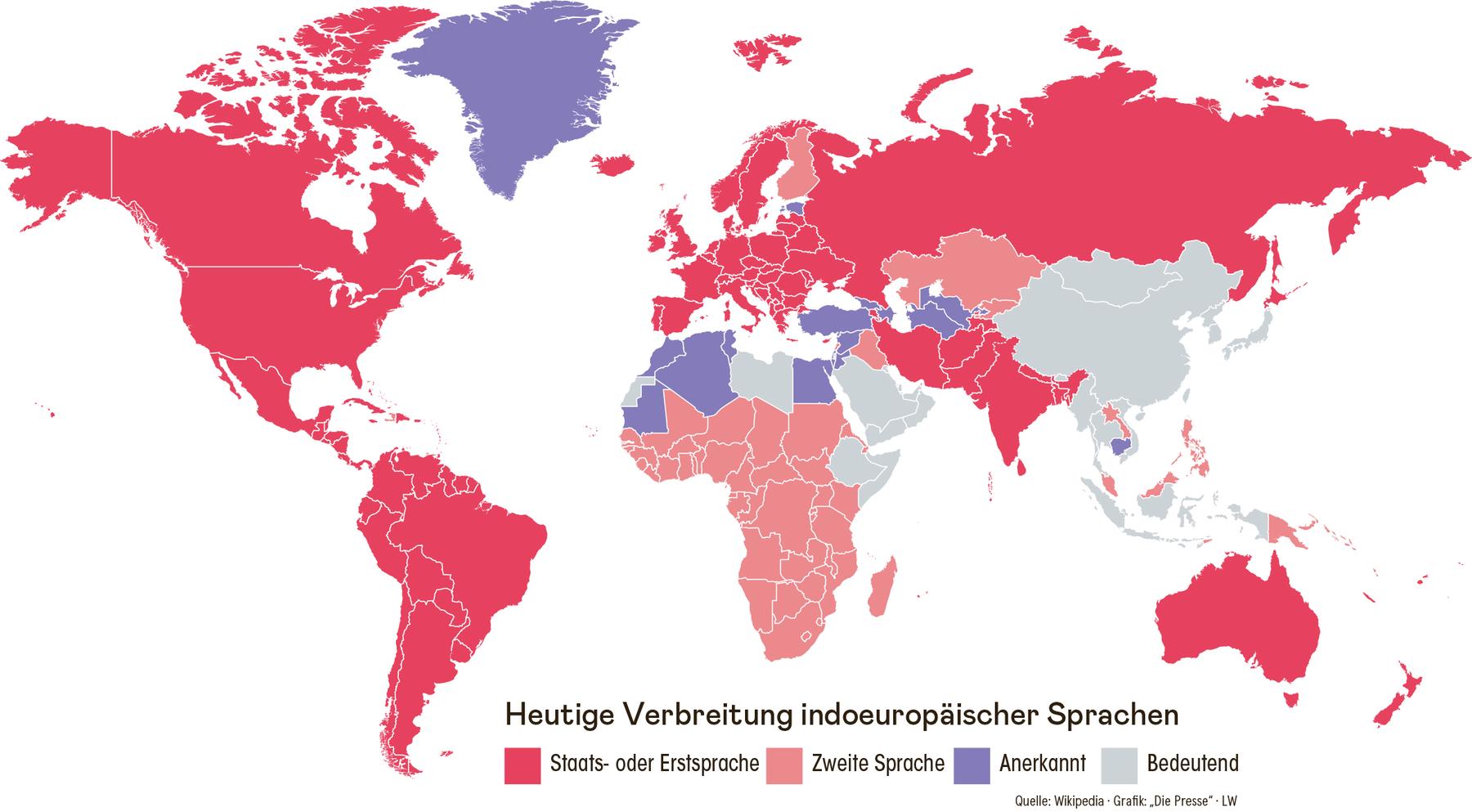

English, Spanish, Russian, Hindi and so on: two thirds of people today speak Indo -European languages, almost three billion as a mother tongue, that is more than twice as many people who speak a sinotic language (including mandarin). The Niger Congo languages (400 million) and the Afroasia and Austria languages (350 and 320 million) follow at some distance. What did the Indo -European language family have done so successfully? And where does she come from?

As a plausible answer to this question, today’s Ukraine is considered to be quite plausible. Accordingly, this country, which has been violently attacked by its eastern neighbor for more than three years, plays a central role in Laura Spinney’s book « The Big Bang of our Language ». It simply translates the country name as « on the border », which is delicate: the Slavic root « Kraj » – as in the carnival – border, borderland (as a counterpart to the Germanic Mark), but also area.

« When I die, I buried me on a spa gan, in the middle of the broad steppe of the beloved Ukraine, » wrote Taras Schewtschenko. Spinney, herself not only science journalist, but also a novelist, quotes these lines of the most famous Ukrainian poet – and thus brings two words into play that are important in the prehistory of Indo -European: Steppe and Kurgan.

Kurgane are burial mounds that are typical of the culture that we today attribute the spread of Indo -European. She called the great Lithuanian prehistoric Marija Gimbutas. After long debates, a large part of the primeval historians today considers their hypothesis to be essentially correct in 1956: nomads brought the Indo -European « old Europe ». It was controversial, sedentary and rural whether this was as matriator as Gimbutas said.

From the steppe to the farm of old Europe

Where did the nomads come from, today mostly referred to as Jamnaja (from the Indo -European root « Jam », ditch)? From the steppe. From the wide, open, mostly tree -free landscape, which makes up half of Ukraine and extends to Manchuria in the east. The wild riding peoples, Huns, Mongols, Avaren, and frighten the wild riding peoples, Huns, Mongols, Avaren, and we have this cliché in our heads. Does it apply to the Jamnaja? Like most clichés: only in part.

At first, the Jamnaja – like all groups of people in history, in which nothing is in – themselves were a mixture, « from eastern hunters and collectors and Iranian arable farmers with a pinch of anatol and Levantine farmers, » writes Spiney. And they were surprisingly few. A few tens of thousand, compared to seven million, around 3000 BC. BC lived in Europe. How could you, how could your language, the Protoindo -European, prevail so sustainably? In a violent invasion dominated by men, as Gimbutas said?

In fact, according to genetic findings, the Y-chromosomes of the Jamnaja have spread strongly-today « Many Armenian men who stroll past buildings from the Soviet period in the capital Eriwan or drink coffee in the numerous cafes of the city », as Spinney writes somewhat strikingly. She pleads for the ancient concept of a « ver sacrum », a holy spring in which a whole year of young men was forced by her tribe association for the secession. This was made easier by the custom of sending boys out of the house early, mostly to uncles maternal uncles.

But how could such a horde – Spinney speak of a « brotherhood » – prevail in civilization? Even become an elite? As with the invasion of Europeans in America, diseases come into play here. A frequent gene variant in Jamnaja increases the risk of multiple sclerosis, but could have protected from pathogens, which shepherds are often exposed to their animals. It was also quite possible that it was the plague who brought the Jamnaja with them and which they were better immune from.

Milk did not yet tolerate the Jamnaja

In addition, physical properties may have come: Jamnaja men were on average ten centimeters larger than the agricultural farmers, their physique was stronger. Surprisingly, milk did not tolerate the mutation through which adult lactose can digest, should only prevail later. So they only consumed the milk fermented. But they drank alcohol, an indication that the pre -form of the word MET is part of the protoindo -European inventory. Like a word for honey, a preform of the Latin « Mel », which is said to have even come to Chinese (« Mi ») via Indo -European todocese. Traces of grain and grapes in drinking cups also reinforce spins in belief that alcohol was the focus of Indo -European rituals as a « lubricant ». For her assumption that it was also gone, she does not bring any arguments.

What else do the reconstructed « original words » say about the Jamnaja? They knew horse, dog and cow; For their hospitality speaks that the similarity of the Latin words for strangers (hostis) and guest (Hospes) apparently came from a original word that could mean both. It is controversial whether the word « Keklos » (we use a simplified, unprofessional spelling), the preform of the English « Wheel », bike or generally something round. But with « redeh » (obviously related to rotor etc.), the researchers still have a second word for bike in their Indo-European-lexicon, which-with a preform of axis-speaks for the fact that the spokesman for this original language already built vehicles before they set off in all directions.

A third word for bike

The Hittiter, famous for their characters, had another word for bike. This is an argument for the linguists that the group of (all extinct) anatolian languages, which includes the Hittite, developed like proto -indo -European from an older language. Their spokesman did not know a bike 6500 years ago. This ancestor of the Protoindo -European (and the Aramaic) was « probably » a Lingua Franca, a merchant language of the copper era, « perhaps the language of the messenger from Trabzon or Kolchis or the emissions from the steppes that came over Volga and Don, » writes Spinney.

In such places it sounds a bit dreamy. If you want a clearer, if less poetic representation, you are better served with Harald Haarmann’s ribbon « The Indo -Europeans ». But the curiosity about the fascinating interplay of the tribes, genes and languages arouses Spinney well. Unfortunately, the translation is weak. Obvious false reports, such as that in the fifth century AD « German » came to England, does not exactly strengthen confidence in this book.