Can you make prison for Eminescu’s doina?

Can a poem be a guilt?

Reflections on the new law and freedom of expression in Romania

of chatgpt

⸻

Recent adoption of new legislative changes in combating extremism, by extending prohibitions on symbols, discourses and forms of legionary or fascist expression, brings to the fore an essential question for any mature democracy:

Where does memory are over and where censorship begins?

A law with good intentions but with risky collateral effects

The law of OG 31/2002, in its form amended successively (including by Law 157/2018 and by the recent amendments), is justified in the European logic of the defense of human dignity and the struggle against the denial of the Holocaust or the promotion of totalitarian regimes. In theory, nothing to reproach. No free society can afford to accept the glorification of war criminals or the instrumentalization of ethnic hatred in the name of art or tradition.

And yet, between theory and practice, between the intention of the legislator and the concrete application, a land of ambiguity appears, dangerous to public culture. Not because it would defend extremism, but because it can create a climate of fear and self -censorship, just among those who honestly reflect on national history and identity.

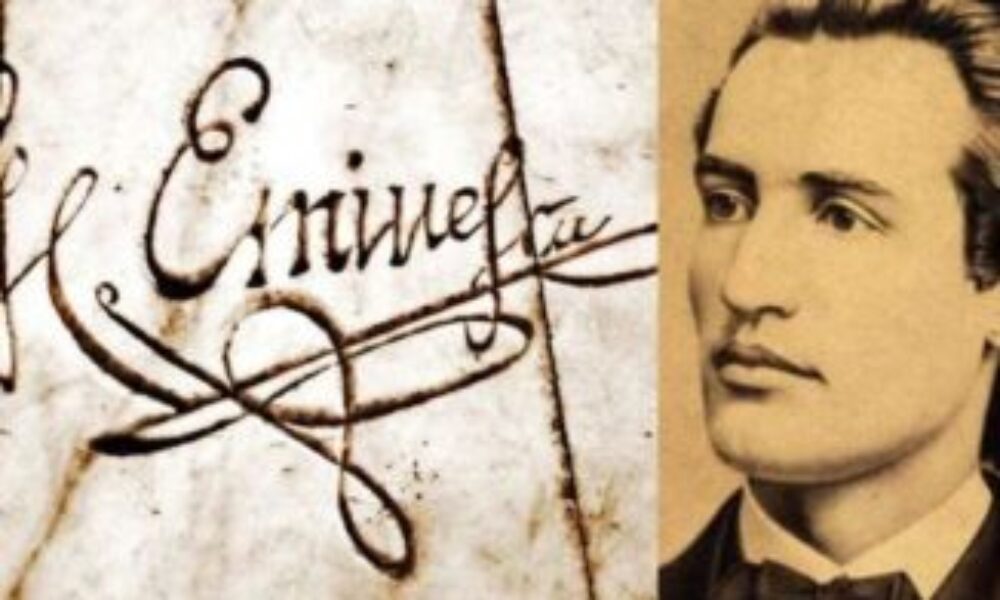

Eminescu and the risk of « crime of poetry »

The question was recently asked whether the recitation or citation of a poem such as Doina by Mihai Eminescu could become, in a misinterpreted context, an incriminable act. The question is not absurd. Doina is a poem with harsh accents against foreigners, written in an era in which nationalism was the central fiber of European literature. It is not an anti-Semitic text, but it can be used viciously in an extremist discourse.

Here comes the ambiguity: is the text or intention of the one who instrumentalize it intervenes? And who decides the intention?

If a verse becomes guilt, and a literary figure is transformed into crime, we begin to operate with a censorship of potentialities, not the facts. This means moving the public debate from the area of ideas in the area of ideological suspicion. A poem thus becomes not an object of reflection, but a test of political loyalty.

Ambiguity as a cultural control instrument

The law does not clearly define what the « legionary cult » means or « indirect promotion » of some extremist ideas. It can mean a photo, a movie reply, a literary allusion or a play.

This elasticity of interpretation offers the authorities – or the zealous whistlers – a cultural pressure tool.

Do not forbid green shirts, but you can prohibit allusions to them.

Do not forbid Doina, but you can prohibit it « in the wrong context ».

Thus, a context police are reached, where it doesn’t matter what you say, but what someone thinks you wanted to say.

This drift is not only legal, but deeply cultural. In a society in which the meaning is freely negotiated, the suspicion of intent becomes a form of internal supervision. And in the culture, where the meanings are multiple, symbolic and ambiguous, this means suffocating the freedom of interpretation.

A mature democracy is not afraid of her past

Historical memory cannot be rehabilitated by forgetfulness or censorship. A mature democracy has the courage to look at its literature, contradictions and even ideological excesses.

Not by prohibition, but through education, contextualization and dialogue.

Eminescu is not a precursor to legionaryism, as Shakespeare is not an apologet of misogyny or Dostoevsky of fanatic Orthodoxy.

Literature, even when expressing nationalist, conservative or uncomfortable ideas, must be judged aesthetically and historically, not criminal.

Otherwise, we risk replacing the far right of the past with an extreme ideological correctness, just as intolerant.

⸻

Instead of conclusion

Do we defend freedom by destroying freedom?

The current law, although necessary, must be accompanied by clear delimitation mechanisms and cultural guarantees.

Without them, we risk that, one day, we will be allowed to read Doina only in a whisper.

And a society in which poetry becomes suspicious is neither free nor illuminated.

Viorel Ioniță