Anglo-Portuguese intrigue at the time Tudor

For three hundred years, a manuscript entitled “A Brief History of the Kings of Portugal” remained untouched by the Archives of the London Antique Society, until the Academics Nuno Vila-Santos and Kate Lowe, from the universities of Lisbon and London, recognized it as a document of great historical importance. Through thorough research, they established that it is the transcription of a 1569/1573 -dated treaty, written as an Aide Memoire to William Cecil (who would later become Lord Burghley), who was the mentor of the private council who advised the monarch Tudor Elizabeth I as secretary of state of foreign affairs and, later, as a high -treasurer.

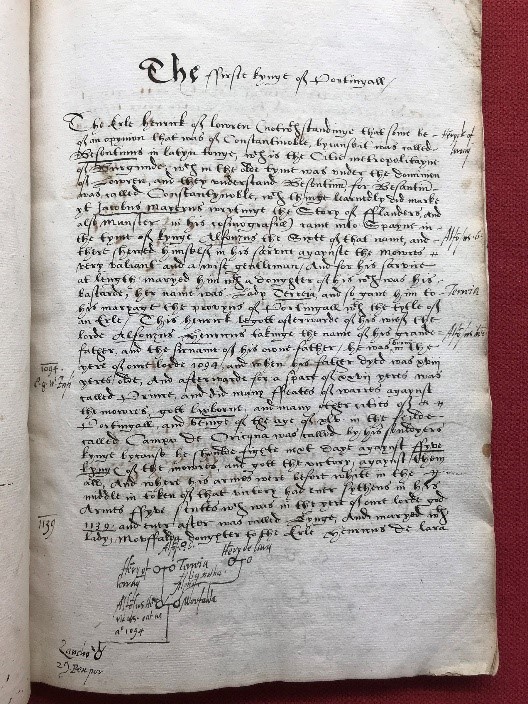

The manuscript is bound in a parchment and consists of twelve pages, two folios and a wide pages that shows in chronological order the genealogy of the royal families, from D. Afonso Henriques to D. Sebastião. The pages feature English water marks and were written in a 16th century cursive letter by a professional copyist who added a commentary that expands the narrative among parentheses. The margins are noted by Lord Burghley, in whose extensive library the manuscript was kept until 1687, when he was sold to the Count of Stamford by two Xelins and eight pence. Also included in this sale works by Portuguese authors of the 16th century, such as Pedro Nunes, Jerônimo Osório and Damião de Gois. These witness Cecil’s political interest in Portugal, which at that time was considered an important European power and often called to arbitrate among the conflicting factions of Spain, France and England.

Teachers list a number of indications that point to the probability that the author is an English trader whose family business was established in Lisbon. It is possible that he would hold an honorary position in the English Ambassador’s team and, as a Roman Catholic of Portuguese, had access to the high society of the Court.

For the first royal dynasty, the manuscript follows a historical format, presenting a brief synopsis of the reign of each monarch, but, after the rise of King John I and the House of Avis, it has much more detail, including references to real indiscretions and intrigues of the court. Thus, it became another intelligence document so that Lord Burleigh could be informed about the consequences of the alliance with England, established by the Windsor Treaty in 1386.

The structure of this alliance was tested during the “Age of Discoveries”, when Portugal (and Spain) defended a policy of MARE CLAUSUM according to which it would have exclusive jurisdiction about the Atlantic Ocean, which bordered with most West Africa. Of course, other European nations, eager to participate in the growing maritime trade, contested this position, and followed several maritime clashes between the Portuguese merchant fleets and the coats.

Catarina da Austria, conductor of Portugal, instructed her main diplomat, João Pereira Dantas, to intervene in these disputes. After Queen Isabel expressly denied the Portuguese monopoly, Dantas sent to the Tudor Court in 1561 a « spy » named Manuel de Araújo, who paved the way for the arrival of Dantas as ambassador. Both made a good impression for their courteous but skilled diplomacy. However, the mercantile navigation pillage continued, and in 1564, Aires Cardoso was sent to file a detailed complaint against John Hawkins, whose fleet of co -workers had caused serious trade disturbances; Especially with the lucrative slave capture business of Guinea, Senegal and Serra Leone and his boarding for Spanish America.

Discussions between the counselors of both countries became increasingly heated and it seemed possible that the treaty be suspended if the scams at sea became a formal war statement. Two other interlocutors were sent from Portugal (Manuel Álvares in 1567 and Francesco Giraldi in 1571) to submit serious complaints that the rule of international law had been disturbed by navigation, but to no avail. In 1568, the Portuguese threatened to get into war and the following year confiscated the properties of the English.

A new English ambassador, a competent diplomat named Thomas Wilson, was sent to Lisbon with instructions to face the storm of discontent negotiating a fairer distribution of passage and commerce rights. It is quite possible that Cecil included in his instructions the requirement to find a secret agent who could provide reports on the real policy and information about the strength of the Portuguese merchant fleet and the royal navy. It seems that the anonymous author of the MS86 may have fulfilled this function, but original copies of his reports have never been found.

The academy.edu published the article written by Kate Lowe and Nuno Vila-Santos as a report of the discoveries. Includes a transcription, which uses 16th century English spelling, including the names of monarchs, such as John to John and Mary to Mary. It is an interesting reading for those difficult times Portugal led the dispute to decide who should « dominate the waves. »

An interesting comparison may be useful with the history of Portugal, written a century later by Manuel de Faria and Sousa, a knight of the Order of Christ. This work offers a much more detailed account of the time in Portugal during the life of the fifteen kings that reigned over Portugal in succession to D. Afonso Henriques and provides many glimpses of social and economic events. For example, the manuscript ends with only a brief account of D. Sebastião, who was still alive when it was written, but Sousa delights in reporting preparations for the ill -fated expedition to Africa, which resulted in the young king straightened with foreign merchants at an 8%reported interest rate. He also finds it necessary to report the young king’s night tours with his page and other young people to the beaches and woods for contemplation!

The details of this essay will be included in a revision of my history of Anglo-Portuguese alliances, which will be republished in the fall of 2025.

Illustrations:

First page of the manuscript

Lord Burghley

King Sebastião

16th century caravel